Economics. It studies economies, of course. Money, GDP, income, spending - all these are part of economics. The economy of a country or the whole world can be analyzed through economics. Those are all big things though. What about on a personal level?

Are you an economist? If your answer is yes, very good. If it’s no, I think you’re wrong.

Economics is not just about money, it’s about decisions. We’re all economists because we make decisions all the time. We use economic principles to make these decisions. Often without realizing it. Rather, economic principles are based on how we think.

Let me share a story of a boy. It has nothing to do with economics. Or so it seems.

Mixed-Up Movie

A young boy goes to the theatre with his parents. He smiles as he walks to the theatre, looking forward to the movie and getting popcorn.

A man in a uniform behind a counter checks out their tickets. He looks up and down, at the tickets and then at the boy. He asks for an ID card for proof of age, and says that the movie is only for adults. The parents try to convince him to let them in, but he doesn't believe that the boy is above 18. After persistent attempts, the man gives up and reluctantly lets them in.

As they walk inside to find their seats, the boy notices some people staring at him, but maybe he's just imagining it?

They all sit down. The lights turn off. The movie starts. The boy laughs at all the hilarious scenes and dialogues. But something bothers him... He ignores it, and continues watching.

A slow-motion scene with dramatic music starts playing. The screen turns black, the lights turn back on. It's the interval. They all step out to buy some popcorn. While waiting in line, the boy feels off. The nagging feeling returns and fills his mind.

It’s hard for him to ignore the feeling now, as there’s no movie to distract him. People’s stares make him uneasy, but also the lying. He cannot enjoy the movie to the fullest. A swarm of thoughts rush through his brain.

I won’t enjoy the rest of the movie

I’ll probably feel bad after finishing the movie too, because we had to lie

I can just watch the movie at home when it releases

I’ll miss the theatre experience though

I can watch another movie some other day

I should go home and enjoy this movie fully, comfortably

Heavy Decision

With all these thoughts in his mind, he didn’t want to continue watching the movie. He decided to leave because he realized that he’d probably feel awkward the entire time. He might feel like he did the wrong thing even after the movie finishes. He looked at the situation, the pros and cons: The movie is enjoyable, but in general, he felt bad about lying. After weighing the two in his mind, the bad feeling was heavier than the movie being enjoyable.

He told his parents he was feeling uncomfortable, and that he wanted to leave. After explaining why, they agreed and left.

Strong Feelings

But was his decision right or wrong? Here, he could use the opportunity cost principle to decide whether or not to leave. In short, the opportunity cost is what you miss out on when you do something. In this scenario, the opportunity cost of watching the movie would be that he can't go back home and do something pleasant.

The boy can also watch the movie when it releases on TV, so he doesn't miss out on the movie either.

The question still remains, is there more benefit to staying in the theatre and finishing the movie, or going back home? This is an example of the cost-benefit principle, which is where you think about whether the benefits are greater than the cost. Similar to pros and cons.

But what are the costs and benefits when watching a movie?

First, costs: money for tickets and the time spent watching the movie. The benefits: entertainment, some laughs, and popcorn.

Because the boy’s parents paid for the ticket, he didn’t really think about the money. But there was an additional cost because he had to lie to get in. That's one more thing to the costs: the bad feeling. Isn't this confusing though? Can feelings be used in economics? Can it be used to decide whether the benefits outweigh the costs?

Well, yes. It can. Otherwise, watching a movie would not be beneficial. “Entertainment” and “some laughs” will have to be removed from the benefits, since they are feelings too. They are good feelings, but still feelings.

It is important to realize that feelings have to be carefully analyzed. For example, would he have stayed if he didn't notice the people staring at him? In this case, probably not. He must have mainly felt bad about lying, but the people staring made him feel worse.

Red and Blue

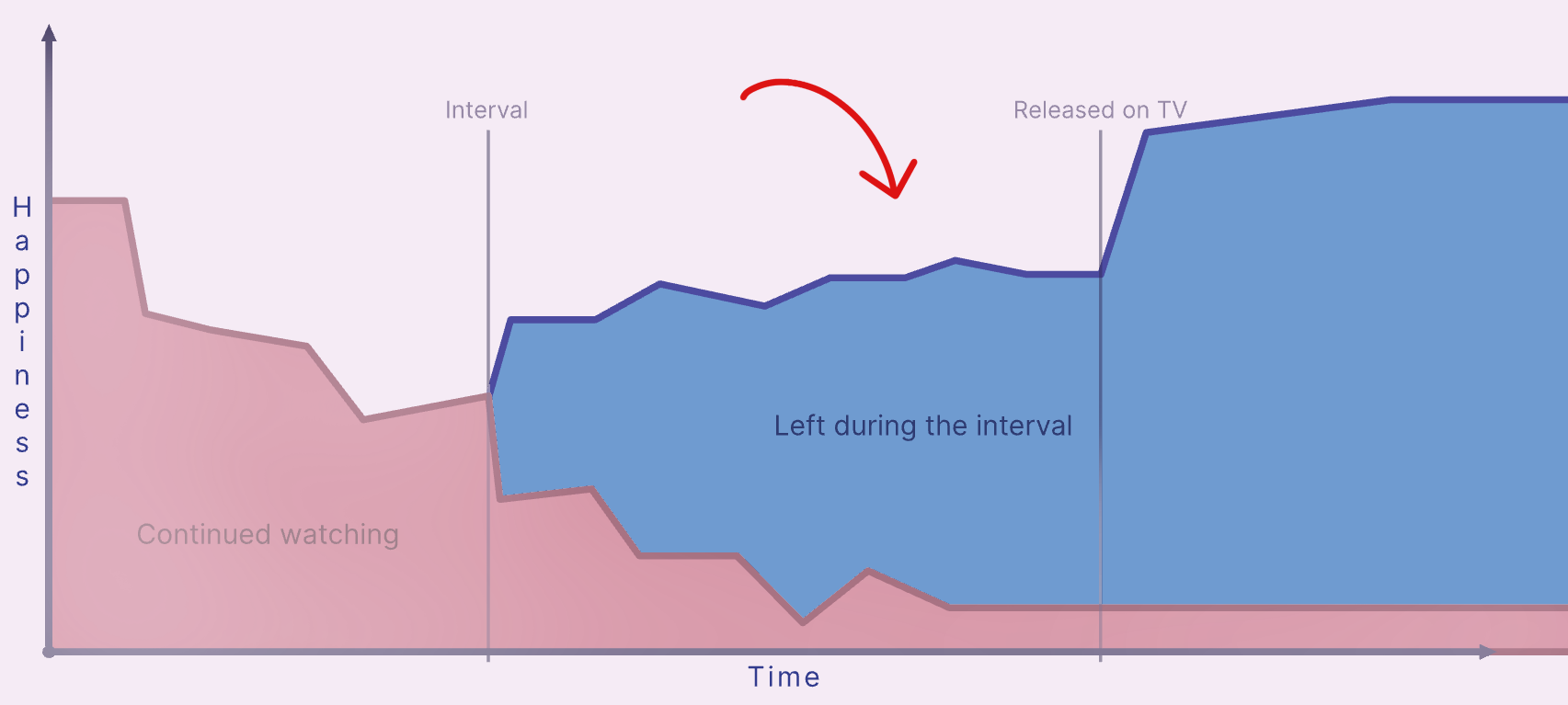

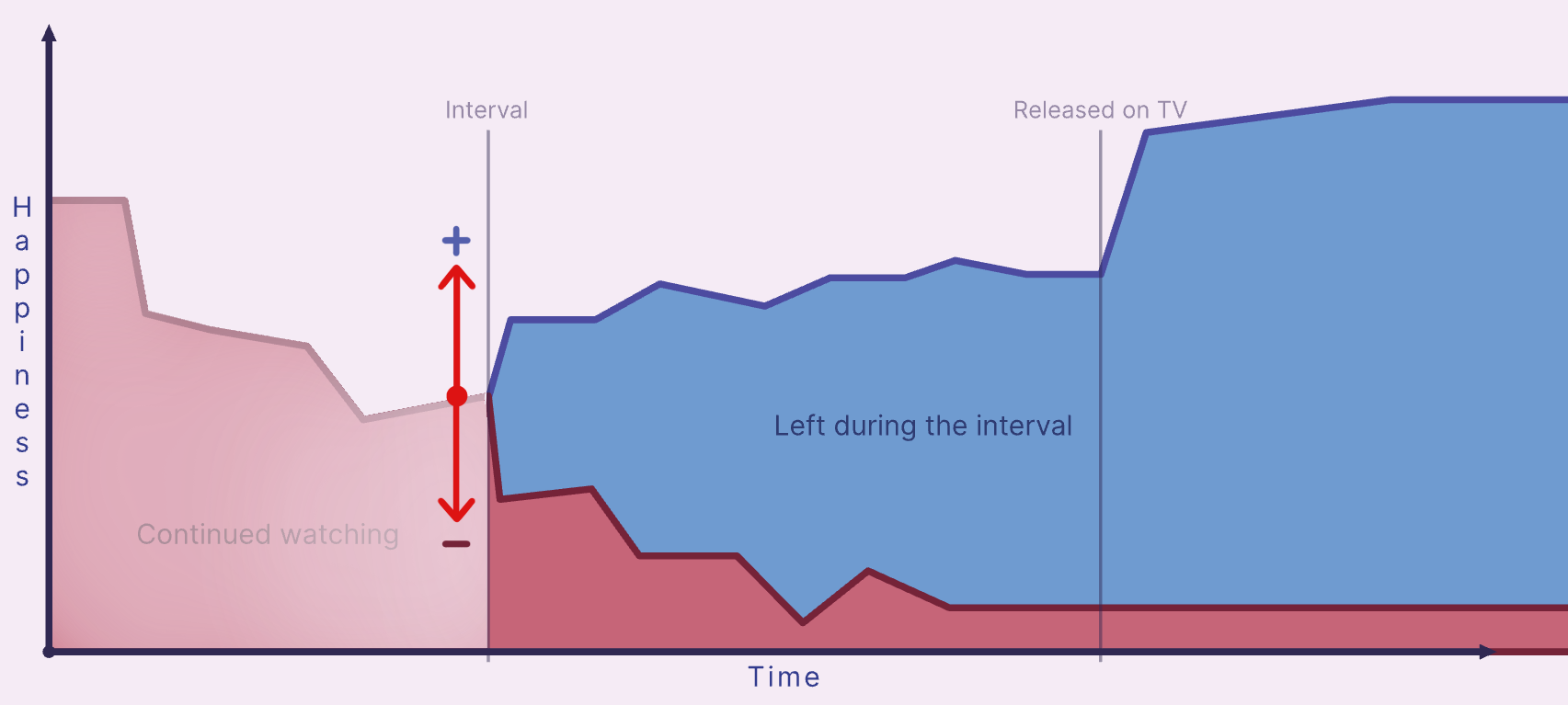

Happiness cannot be measured, so it’s just an approximation of how the boy was feeling in order to visualize economic principles, not an accurate graph

The graph above shows the opportunity cost principle and the cost-benefit principle again.

First up, the opportunity cost. The arrow points to what the boy misses out on if he continues watching the movie. He misses out on going back home and doing something else.

Next, the cost-benefit principle. The arrows show that if he continues watching, his happiness goes down. But, if he leaves and returns back home, his happiness goes up.

It’s clear that the benefits of leaving exceed that of staying.

Time to be Spent

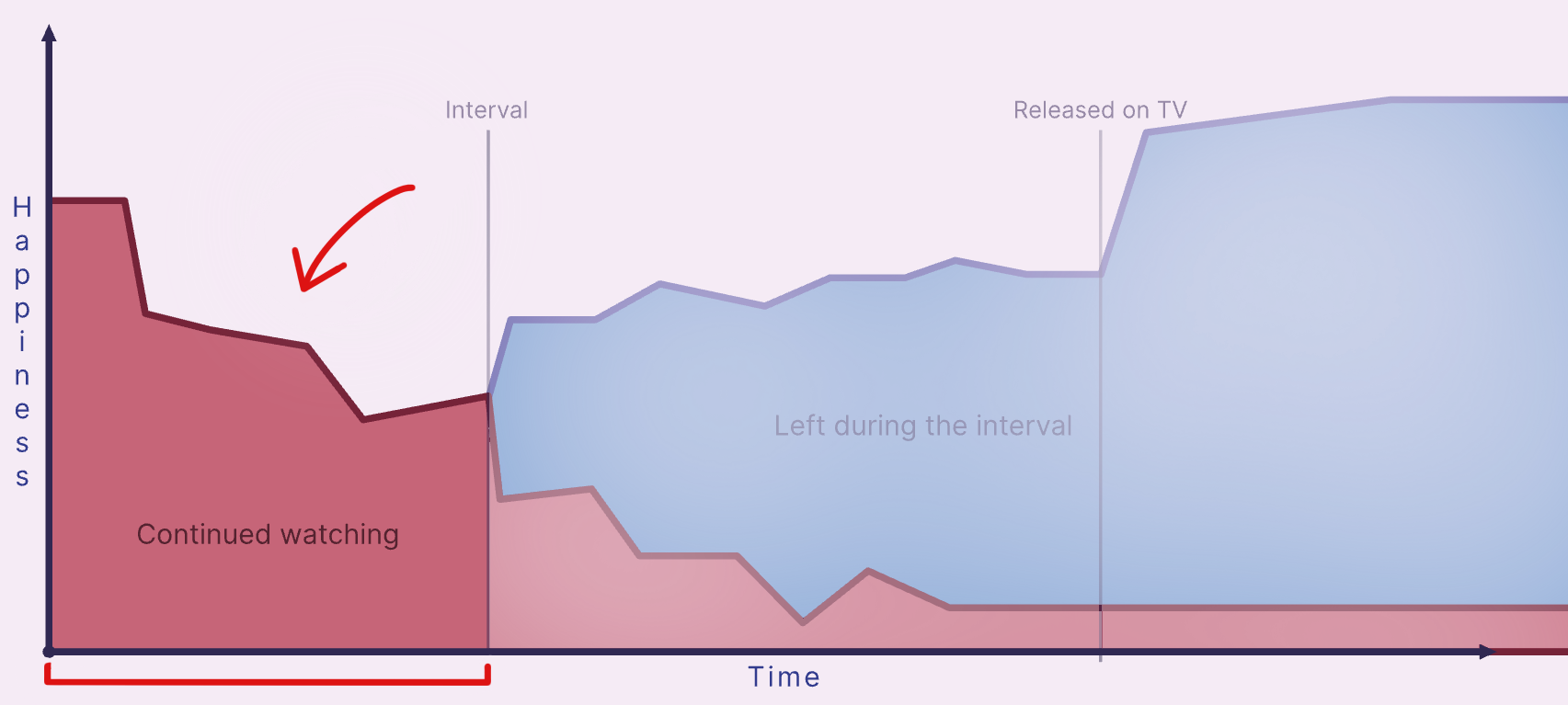

There is one more thing that is hidden in this graph. It’s the sunk cost principle. A sunk cost is something that has been spent, and cannot be recovered.

In this case, the sunk cost would be the time spent watching the movie, which you can see in the image above, and the money for the tickets. Again, the boy isn’t paying for the tickets, so he doesn’t worry about the money. But, even if he did, should he think about the sunk costs?

Just because the time and money has been spent to watch this movie, should he continue watching it so that they don’t go to waste? Most likely not. Because the decision isn’t about what has already happened in the past, which cannot be changed. It is about the present.

The sunk cost is gone. The cost has already sunk, there is no need to think about it when it’s done, the only thing that matters in this scenario is the present.

There is some time after the interval, where anything can be done. Here is where the opportunity cost principle can be used: what else can he do instead of finishing the movie?

In this case, he left and had lunch at a restaurant, then went back home and relaxed!

Epilogue

A few months later, the movie releases on OTT. This time, the boy has no need to lie about anything, and he watches the movie comfortably. There's no popcorn and large screen, but the movie is as hilarious as it was in the theatre. He's laughing again, at the scenes he already saw and at the new ones after those.

The movie finishes. The boy feels great, he watched the entire movie with only positive feelings. Sure, it wasn't the same experience as the theatre, but he knew that when he made his decision. He's happy with how this experience was, even if it wasn't as immersive as the theatre.

I have made a SocratiQ exploration where you can gain an intuition about economics using real-world scenarios. SocratiQ asks you questions about economics - using real-world examples - which you can answer at your own pace. You can also look at my exploration where I have answered a few of the questions. Feel free to fork it and explore along with me.

What About the Lying?

The boy and his parents had to lie to get in and watch the movie. The boy did choose to leave during the interval, but regardless, was lying the right thing to do? Was it in order? The uniformed man was the authority, and he said that they couldn’t watch the movie. But they got in anyways. Was it the right thing to do do defy authority? This has nothing to do with economics, so I’ve written a different article about Order & Authority.